Students investigate scatter plots as a method of visualizing the relationship between two quantitative variables. In the programming environemt, points on the scatter plot can be labelled with a third variable!

Lesson Goals |

Students will be able to…

|

Student-facing Lesson Goals |

|

Materials |

|

Preparation |

|

- explanatory variable

-

any variable that could impact the "response variable", generally plotted on the x-axis of a scatter plot

- response variable

-

the variable in a relationship that is presumed to be affected by the explanatory variable, generally plotted on the y-axis of a scatter plot

- scatter plot

-

a display of the relationship between two quantitative variables, graphing each explanatory value on the x axis and the accompanying response on the y axis

🔗Relationships Between Columns 15 minutes

Overview

Students are introduced to questions that ask about the relationship between one quantitative column and another.

Launch

Can animals' weights help explain why some are adopted quickly while others take a long time? What other factors explain why one pet gets adopted right away, and others wait months?

Theory 1: Smaller animals get adopted faster because they’re easier to care for.

How could we test that theory? Bar and pie charts are great for showing us frequencies or percentages in a categorical column. Histograms and box plots are great for showing us the shape, center, and spread of a single quantitative column. But none of these displays will help us see connections between two quantitative columns.

Investigate

-

Take a few minutes to look through the whole dataset, and see if you agree with Theory 1.

-

Could any of our visualizations or summaries provide evidence for or against the theory?

-

Write down your hypothesis on (Dis)Proving a Claim, as well as a theory about how we could use this dataset to see if you’re right.

Synthesize

We’ve got a lot of tools in our toolkit that help us think about an entire column of a dataset:

-

We have ways to find measures of center and spread for a given quantitative column.

-

We have visualizations that let us see the shape of values in a quantitative column.

-

We have visualizations that let us see frequencies or percentages in a categorical column.

What columns is this question asking about?

🔗Making Scatter Plots 20 minutes

Overview

Students are introduced to scatter plots, which are visualizations that show the relationship between two quantitative variables. They learn how to construct scatter plots by hand, and in Pyret.

Launch

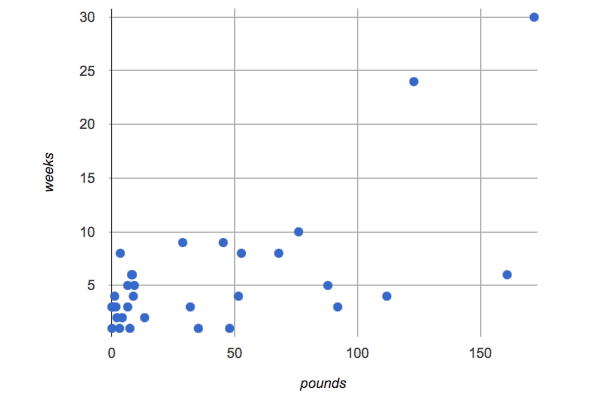

This question is asking about two columns in our dataset. Specifically, it’s asking if there is a relationship between pounds and weeks.

Before we can draw a scatter plot, we have to make an important decision: which variable is explanatory and which is response? In this case, are we suspecting that an animal’s weight can explain how long it takes to be adopted, or that how long it takes to be adopted can explain how much an animal weighs?

The first of these makes sense, and reflects our suspicion that weight plays a role in adoption time. The convention is to use the horizontal axis for our explanatory variable and the vertical axis for the response variable. Each row in the data set will be a point on the scatter plot with pounds for x and weeks for y.

Investigate

We will produce our scatter plot by graphing each animal’s pounds and weeks values as a point on the x and y axes.

Complete Creating a Scatter Plot in your Student Workbook.

Teaching Tip Divide the full table up into sub-lists, and have a few students plot 3-4 animals on the board. This can be done collaboratively, resulting in a whole-class scatterplot! |

-

Open your “Animals Starter File”. (If you do not have this file, or if something has happened to it, you can always make a new copy.)

-

Make a scatter plot that displays the relationship between weight and adoption time.

-

Are there any patterns or trends that you see here?

-

Try making a few other scatter plots, looking for relationships between other columns in the

animals-table.

Synthesize

Have students share their observations. What trends do they see? Are there any points that seem unusual? Why?

🔗Looking for Trends 20 minutes

Overview

Students are asked to identify patterns in their scatter plots. This activity builds towards the idea of linear associations, but does not go into depth (as the following lesson does).

Launch

Shown below is a scatter plot of the relationships between the animals' age and the number of weeks it takes to be adopted.

-

Can you see a “cloud” around which the points are clustered?

-

Does the number of weeks to adoption seem to go up or down as the weight increases?

-

Are there any points that “stray from the pack”? Which ones?

Teaching Tip Project the scatter plot at the front of the room, and have students come up to the plot to point out their patterns. |

A straight-line pattern in the cloud of points suggests a linear relationship between two columns. If we can pinpoint a line around which the points cluster (as we’ll do in a future lesson), it would be useful for making predictions. For example, our line might predict how many weeks a new dog would wait to be adopted, if it weighs 68 pounds.

Do any data points seem unusually far away from the main cloud of points? Which animals are those? These points are called unusual observations. Unusual observations in a scatter plot are like outliers in a histogram, but more complicated because it’s the combination of x and y values that makes them stand apart from the rest of the cloud.

Unusual observations are always worth thinking about

-

Sometimes they’re just random. Felix seems to have been adopted quickly, considering how much he weighs. Maybe he just met the right family early, or maybe we find out he lives nearby, got lost and his family came to get him. In that case, we might need to do some deep thinking about whether or not it’s appropriate to remove him from our dataset.

-

Sometimes they can give you a deeper insight into your data. Maybe Felix is a special, popular (and heavy!) breed of cat, and we discover that our dataset is missing an important column for breed!

-

Sometimes unusual observations are the points we are looking for! What if we wanted to know which restaurants are a good value, and which are rip-offs? We could make a scatter plot of restaurant reviews vs. prices, and look for an observation that’s high above the rest of the points. That would be a restaurant whose reviews are unusually good for the price. An observation way below the cloud would be a really bad deal.

Investigate

For practice, consider each of the following relationships, always expressed as "response variable vs explanatory variable". First think about whether you’d expect the variables to be related, then make the scatterplot to see if your hunch seems correct. If you see any unusual observations, try to explain them!

-

The

poundsof an animal vs itsage -

The number of

weeksfor an animal to be adopted vs its number oflegs -

The number of

legsvs theageof an animal. -

Do you see a linear (straight-line) relationship in any of these, evidenced by a cloud of points that’s clearly rising or falling from left to right? Are there any unusual observations?

Synthesize

Debrief, showing the plots on the board. Make sure students see plots for which there is no relationship, like the last one!

Theory 2: Younger animals get adopted faster because they are easier to care for.

It might be tempting to go straight into making a scatter plot to explore how weeks to adoption may be affected by age. But different animals have very different lifespans! A 5-year-old tarantula is still really young, while a 5-year-old rabbit is fully grown. With differences like this, it doesn’t make sense to put them all on the same scatter plot. By mixing them together, we may be hiding a real relationship, or creating the illusion of a relationship that isn’t really there! What should we do to explore this theory?

These materials were developed partly through support of the National Science Foundation,

(awards 1042210, 1535276, 1648684, and 1738598).  Bootstrap by the Bootstrap Community is licensed under a Creative Commons 4.0 Unported License. This license does not grant permission to run training or professional development. Offering training or professional development with materials substantially derived from Bootstrap must be approved in writing by a Bootstrap Director. Permissions beyond the scope of this license, such as to run training, may be available by contacting contact@BootstrapWorld.org.

Bootstrap by the Bootstrap Community is licensed under a Creative Commons 4.0 Unported License. This license does not grant permission to run training or professional development. Offering training or professional development with materials substantially derived from Bootstrap must be approved in writing by a Bootstrap Director. Permissions beyond the scope of this license, such as to run training, may be available by contacting contact@BootstrapWorld.org.