Overview

Learning Objectives

Evidence Statements

Product Outcomes

Materials

Preparation

Seating arrangements: ideally clusters of desks/tables

- Right now in the Ninja Cat game, nothing happens when the player collides with another game character. We need to write a function change that. This is going to require a little math, but luckily it’s exactly the same as it was in Bootstrap:1.

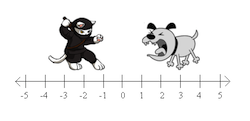

In the image above, how far apart are the cat and dog?

If the cat was moved one space to the right, how far apart would they be?

What if the cat and dog switched positions?

In one dimension, such as on a number line, finding the distance is pretty easy. If the characters are on the same line, you just subtract one coordinate from another, and you have your distance. However, if all we did was subtract the second number from the first, the function would only work half the time!When the cat and dog were switched, did you still subtract the dog’s position from the cat’s, or subtract the cat’s position from the dog’s? Why?

Draw the number line on the board, with the cutouts of the cat and dog at the given positions. Ask students to tell you the distance between them, and move the images accordingly. Having students act this out can also work well: draw a number line, have two students stand at different points on the line, using their arms or cutouts to give objects of different sizes. Move students along the number line until they touch, then compute the distance on the number line.

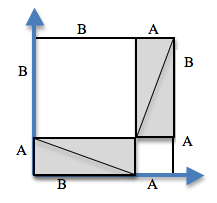

For any right triangle, it is possible to draw a picture where the hypoteneuse is used for all four sides of a square. In the diagram shown here, the white square is surrounded by four gray, identical right-triangles, each with sides A and B. The square itself has four identical sides of length C, which are the hypoteneuses for the triangles. If the area of a square is expressed by , then the area of the white space is .

For any right triangle, it is possible to draw a picture where the hypoteneuse is used for all four sides of a square. In the diagram shown here, the white square is surrounded by four gray, identical right-triangles, each with sides A and B. The square itself has four identical sides of length C, which are the hypoteneuses for the triangles. If the area of a square is expressed by , then the area of the white space is . By moving the gray triangles, it is possible to create two rectangles that fit inside the original square. While the space taken up by the triangles has shifted, it hasn’t gotten any bigger or smaller. Likewise, the white space has been broken into two smaller squares, but in total it remains the same size. By using the side-lengths A and B, one can calculate the area of the two squares.

By moving the gray triangles, it is possible to create two rectangles that fit inside the original square. While the space taken up by the triangles has shifted, it hasn’t gotten any bigger or smaller. Likewise, the white space has been broken into two smaller squares, but in total it remains the same size. By using the side-lengths A and B, one can calculate the area of the two squares.

The smaller square has an area of , and the larger square has an area of . Since these squares are just the original square broken up into two pieces, we know that the sum of these areas must be equal to the area of the original square:

The smaller square has an area of , and the larger square has an area of . Since these squares are just the original square broken up into two pieces, we know that the sum of these areas must be equal to the area of the original square: